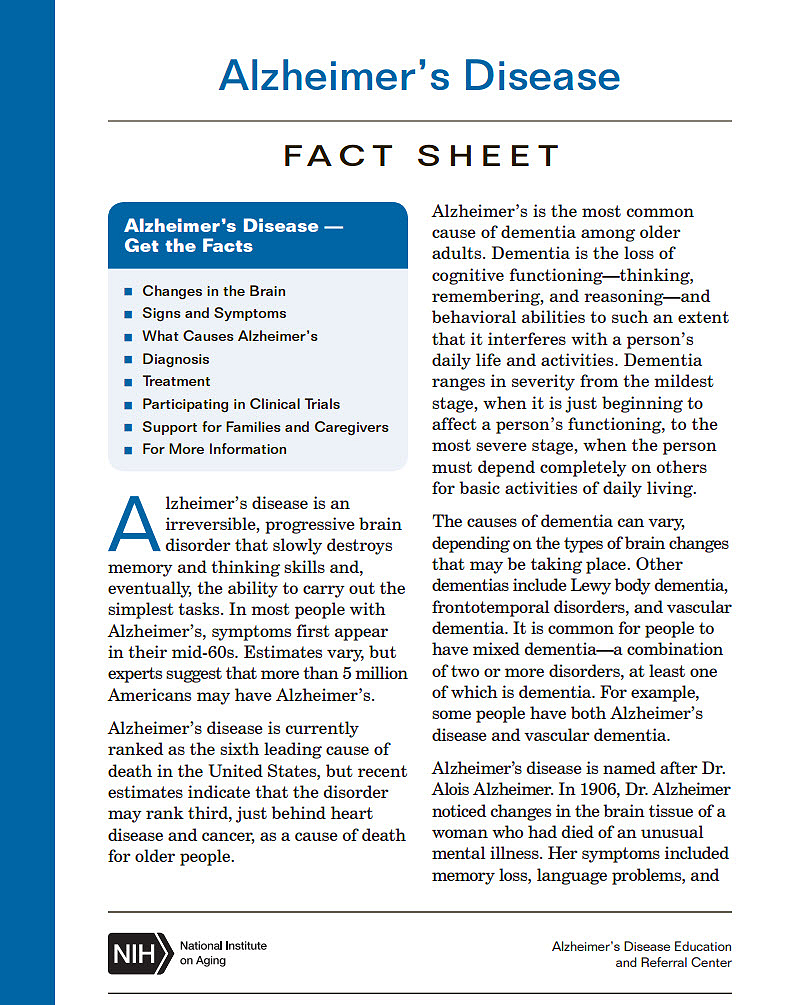

(NPR) Greg O’Brien was diagnosed with early-onset Alzheimer’s disease eight years ago. He has written about his experiences with the disease.

The first problem with the airplane bathroom was its location.

It was March. Greg O’Brien and his wife, Mary Catherine, were flying back to Boston from Los Angeles, sitting in economy seats in the middle of the plane.

“We’re halfway, probably over Chicago,” Greg remembers, “and Mary Catherine said, ‘Go to the bathroom.’ ”

“It just sounded like my mother,” Greg says. So I said ‘no.’ “

Mary Catherine persisted, urging her husband of 40 years to use the restroom. People started looking at them.

“It was kind of funny,” says Greg.

Mary Catherine was more alarmed than amused. Greg has early-onset Alzheimer’s, which makes it increasingly hard for him to keep track of thoughts and feelings over the course of minutes or even seconds. It’s easy to get into a situation where you feel like you need to use the bathroom, but then forget. And they had already been on the plane for hours.

Finally, Greg started toward the restroom at the back of the plane, only to find the aisle was blocked by an attendant serving drinks. Mary Catherine gestured to him.

“Use the one in first class!”

At that point, on top of the mild anxiety most people feel when they slip into first class to use the restroom, Greg was feeling overwhelmed by the geography of the plane. He pulled back the curtain dividing the seating sections.

“This flight attendant looks at me like she has no use for me. I just said ‘Look, I really have to go the bathroom,’ and she says ‘OK, just go.’ “

Before Greg had Alzheimer’s, he would have discreetly made his way up the aisle, used the bathroom and gone back to his seat. Now, no part of that was possible. He had no idea where the bathroom was. Even after the crew member pointed to the front of the plane, he was still confused.

There were two doors.

He moved down the aisle, buying time, feeling the flight attendant watching him. The middle door was larger. He put his hand on it.

Immediately, he knew it was wrong – he had touched the cockpit door. The flight attendant was at his side. He apologized. She asked him to please step away from the door.

“I’m sorry,” Greg told her. “I have a problem. I got some Alzheimer’s.

“I didn’t get to pee,” he says now. “But I think I was lucky nothing bad happened.”

Greg unwinds a hose while doing some yardwork. Along with his failing memory, Greg has been experiencing secondary symptoms including paranoia, depression and slow healing.

Eight years after he was diagnosed with early-onset Alzheimer’s disease, the 67-year-old’s memory is failing slowly and irreversibly. But, increasingly, it is his other symptoms that interrupt his day-to-day life as a writer, father, husband and now grandfather.

Some symptoms he is struggling with have largely unknown mechanisms. His depressed immune system, for example, is likely related to his Alzheimer’s disease, but researchers are still unsure exactly how. Same with the exact relationship between the Alzheimer’s and the numbness he feels in his hands and feet.

But many of the symptoms he experiences have clear links to the disease — things like rage, paranoia, depression and incontinence.

And he thinks that a lot of people who are open about some Alzheimer’s symptoms are uncomfortable talking about things like incontinence. He makes an extra effort to be open about his symptoms and joke about the parts of his life that are still funny.

“You’ll never see me with tan pants. I always have an extra pair of pants in the car,” he says, laughing a little. “I’m not trying to gross anyone out, but that’s my life today.”

“You don’t die of Alzheimer’s,” Greg says. “You die of everything else. But first, you live with it all. Alzheimer’s is not your grandfather’s disease.”

Prescription Side Effects

“I refuse to take this one because it makes me loopy,” Greg explains, standing at his kitchen sink pointing at one of the pill bottles lined up on the windowsill.

He reaches for another bottle.

“I call these ones my smart pills,” he says, struggling with the childproof top. “These goddamn things,” he grunts, the water running into the sink.

He extracts a pill and tosses it into his mouth, dipping his head to drink from the faucet.

He smiles. “Not always the best manners, I know.”

Although there is no drug to slow or stop the inevitable progression of Alzheimer’s, people like Greg, who was diagnosed with the early-onset form of the disease, often take multiple drugs to treat the symptoms. Greg has prescriptions for four drugs he’s supposed to take every day: two to combat dementia and other cognitive symptoms, and two antidepressants, Celexa and trazodone.

Trazodone is the one Greg refuses to take. Along with the second antidepressant, it’s meant to help him deal with the depression and suicidal thoughts that he has been experiencing on and off since he was diagnosed.

“In Alzheimer’s disease, you’re not just affecting the ability to remember things and learn things, but you’re also affecting parts of the brain that control mood,” says Rudy Tanzi, an Alzheimer’s researcher and assistant professor at Harvard Medical School.

He says Alzheimer’s affects the frontal lobe of the brain, which is involved in the ability to show restraint.

As the frontal lobe degenerates, it becomes easier to give into desires and fear. Many people get depressed, angry and anxious.

Celexa and other so-called mood stabilizers can help reduce that stress, agitation and depression. But research has also shown that such drugs can make it more difficult to think and focus, which in turn makes it difficult to do things like write.

And Greg is a writer. For years, he worked at newspapers and magazines in Boston and on Cape Cod. After his diagnosis, he wrote an autobiography, On Pluto: Inside The Mind Of Alzheimer’s, a second edition of which will be distributed by Viking/Random House in July. He still works as a freelance writer and editor, in part because he says his family needs the income.

And so, for now, he has decided to live with rage and depression, rather than compromise his ability to write.

Not everyone agrees with his choice to forgo some medication. His wife, Mary Catherine, and his son Conor, who works as a full-time assistant for Greg, have their own opinions.

This spring, Mary Catherine talked to one of Greg’s doctors.

“I was asking for some medication so I wouldn’t regret being married for 40 years,” she says, half-joking as she unloads groceries.

She has said that one of the unexpected parts of her husband’s Alzheimer’s is that it has brought them closer to each other, but everyone in the family seems to agree that his rage is still particularly difficult to handle.

“They have to put up with this,” Greg acknowledges, “that’s not fair.”

“I understand,” he continues, his smile fading.

“I’m worried about not being able to control the rage, and it’s getting to the point where it’s upsetting.

My son doesn’t even want to watch a Celtics game with me anymore, because if someone dribbles the wrong way, it’s ticking [me off], particularly if it’s at night.”

“How do I get a handle on it? I’m not quite sure. But I want to write. That’s what keeps me whole. That’s what makes me who I am.”

Sadness replaces defiance in his voice.

“I don’t know. I don’t want to lose any more than is already being taken from me,” he says.

“It means I become less of me.”

“He’s stalking me”

“That guy is watching me. I’ve got no freaking idea who he is,” Greg says, looking over his shoulder at a man sitting a few tables away.

The outdoor patio at a café in Orleans, Mass., is half full. It’s early afternoon on a Thursday.

A few minutes ago, the mystery man walked by and said hello to Greg. Now, as Greg looks over at him, he is smiling.

“He gave me a big hug, put his arm around me. Obviously I’ve known him for 20 years,” says Greg, his voice low.

“He’s sitting there on the steps now waiting for me. He’s waiting for me. He’s stalking me.”

At some level, he knows it’s not a rational fear. Sitting outside, a few minutes from his home on a spring day, Greg O’Brien is not in danger. But he is a man without a map, adrift in a sea of seemingly random information that has no context or way to order itself in his mind.

And so, in place of rational reaction to a man saying hello to him, Greg begins to worry he is being watched by a potential assassin.

In Alzheimer’s, “your brain can no longer regulate how what you hear and what you see at any given moment is integrated into a map of the world,” explains Tanzi.

“The paranoia is coming because you’re really experiencing in a sensory way things that are happening only in your own mind.”

But, in some ways, Greg is still the gregarious writer and father of three who frustrated his family with his endless gabbing when they went out to eat. Now, that part of his personality cuts through the paranoia, and he stands up and walks toward the stranger.

And this, says Tanzi, is absolutely the best way to react to Alzheimer’s disease.

“Greg is absolutely an outlier,” he says (the two met through the Boston-based Cure Alzheimer’s Fund).

“Having the motivation and the incentive and the drive every day to say, ‘Look, I have a disease. It’s progressive and it’s going to keep going. But I have a chance every day to try to fight it.’ Having that sense of purpose literally turns on the frontal cortex,” he explains.

“It provides you with meaning, and purpose and self-awareness. It’s brave.”

Greg approaches the mystery man.

“Hi, I’m Greg O’Brien. Do we know each other?”

Yes, the stranger replies gently. He is an old friend, a colleague from back when Greg worked at the The Cape Codder newspaper. He has known Greg for more than 20 years. He is a frequent confidant these days, though mostly by email, he says.

He thanks Greg for the help and support with his aging mother, who suffered memory loss. And they sit and chat, like the old friends they are.

http://www.npr.org/sections/health-shots/2017/06/24/525887392/more-than-memory-coping-with-the-other-ills-of-alzheimers

© 2017 npr

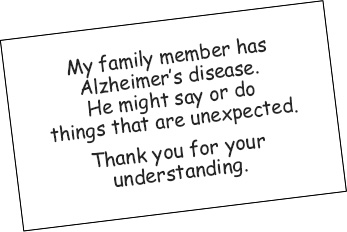

Remember that you can use a business-size card, as shown below, to tell others about the person’s disease. Sharing the information with store clerks or restaurant staff can make outings more comfortable for everyone.

Remember that you can use a business-size card, as shown below, to tell others about the person’s disease. Sharing the information with store clerks or restaurant staff can make outings more comfortable for everyone.